Why cognitive science matters in education: three reasons

My perspective on why the science of learning is important for teachers

This is my first post on Substack, after a while of writing much less. I’m taking this fresh start as an opportunity to return to the basics, and hopefully continue from there by writing more about bridging the cognitive science literature with practical takeaways for teaching.

When I introduce the “science of learning” to educators, the first question that must be addressed is: Why? Why is this knowledge necessary? Beyond being interesting, how does it actually help a teacher become more effective?

Since this is not a trivial question, it deserves a thoughtful answer. Here is mine. It has three parts.

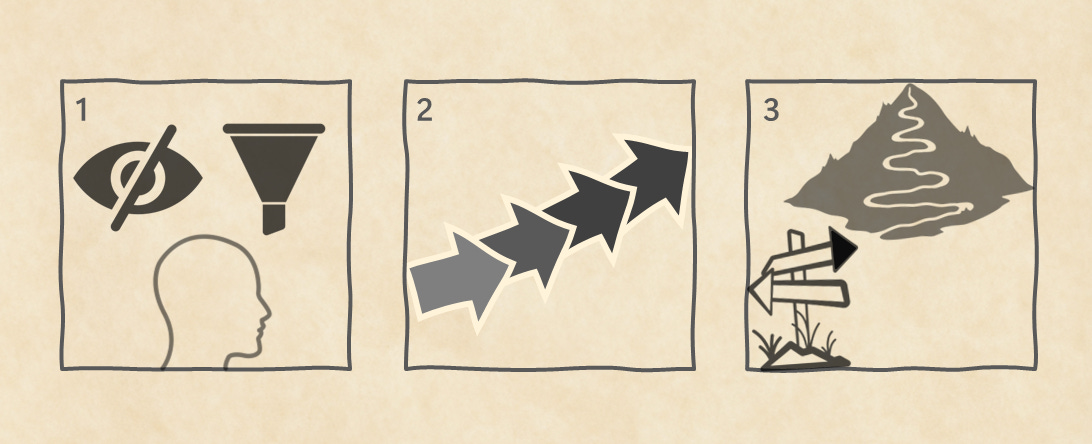

1. Functions and Limitations

Understanding how our mind works allows us to teach in ways that align with our cognitive functions and limitations. This is especially important in challenging learning situations when we want to maximise our cognitive abilities. Most learning environments, K–12 and beyond, are, and should be, challenging. What follows applies primarily to such contexts.

To keep it simple, let’s consider two main cognitive areas: the systems that process information - attention and working memory, and the systems that store and retrieve knowledge, collectively referred to as long-term memory.

The processing systems

Attention and working memory (WM) are essential for our ability to perceive, select, and process information from the environment, alongside relevant prior knowledge. This is a central function: any information incoming from the environment must be processed to potentially become our own knowledge down the line.

This functionality serves us well even without understanding it. The goal is to understand and manage those occasions when it doesn’t. The primary limitation, as most readers likely know, is that processing capacity is strictly limited to just a few items at once. The time that the information can be sustained is also highly limited: the items disappear within seconds if not actively rehearsed. As this mental processing is necessary (but not sufficient) for learning, this limitation creates a major bottleneck that limits our processing capacity and thus shapes our whole experience.

We can only process new items at a given capacity, while the environment always includes many more items than we can process. Filtering and focusing are constantly necessary.

Every item we process consumes “bandwidth.” When unnecessary information enters the loop, it creates interference that can stall or even shut down the learning process entirely.

We can control some aspects of the “filter and focus” process, but some of it is involuntary - hence intereferences are always there to deal with.

Sometimes, at the time of learning, we don’t know what is necessary and what is not. As a result, even the filtering processes we are able to control, may create interference.

All this makes it challenging and costly to manage the processing of new information, especially when it is mostly new and relatively complex.

What makes this process easier - or at least more manageable?

An environment that is intentionally arranged and designed for learning: one in which filtering, focusing, processing, retrieval of relevant prior knowledge, pacing, and alignment are all managed and guided toward a well-defined purpose.

Prior knowledge and experience: the more we know about what we are about to process and the more experience we have in handling similar tasks, the easier the process is and the more we can manage it independently.

Takeaway: Teachers are there to help learners with both 1 & 2. They design sequences that support learning closely in the initial stages. And gradually shift to teach them how to manage their own learning, as their knowledge and experience grow. Fortunately, these lenses of approaching these limitations have gradually become known and more importantly, applied, thanks to the seminal work by Kirschner, Sweller & Clark, 2006 and many that followed.

The long-term memory systems

While working-memory limitations are increasingly acknowledged in education, the functions and limitations of long-term memory systems are often less explicit. The different long-term systems enable us to store knowledge of various forms (e.g. procedural, episodic, and semantic) for future use. The conscious parts of it allow us to mentally time-travel (Tulving, 1985) - an amazing phenomenon that should not be taken for granted: It is the source of our intelligence, our creativity, our behaviour, and our autobiographical sense.

But what are the limitations of long-term memory systems?

In short, long-term memory is not transparent. We can mentally time-travel, but we cannot predict if a newly learned idea will be available for a future trip. Will we be able to retrieve it? If we can retrieve it right now, will it still be possible in a month? If we cannot retrieve it now, is it really gone, or is it just a temporary block?

To find out, we have no option but trial and error. We have to test our memory to know whether it is there for us and in what form.

Daniel Schacter identified seven “Sins” of memory, already in 1999 (Schacter 1999,2022) - the first three are sins of omission, or reasons for retrieval failure:

Transience - decreasing accessibility of information over time

Absent-mindedness - inaccessibility due to the absence of retrieval cues

Blocking - temporary inaccessibility of information that is stored in memory

Long-term memory can fail in even more ways! Sometimes it’s inaccurate or even distorted. Schacter further identifies four sins of commission :

Misattribution - attribution of a memory or an idea to the wrong source

Suggestability - implanted memories that result from suggestion or misinformation

Bias - retrospective distortion produced by current knowledge, beliefs or feelings

Persistence - intrusive or pathological remembrance of events

This last group of “sins” highlight the fact that we are also unaware of how our memory changes over time and by various interacting factors.

On top of that, there are types of memories that are almost entirely unconscious - we are either unaware or unable to describe them explicitly (referred to as nondeclarative or implicit long-term memory), such as procedural memory, habit formation and conditional responses. Nonetheless, they play a major role in our decisions and behaviour, and function constantly in parallel to our declarative or explicit long-term memory systems (memory for facts, ideas and events).

To summarise, long-term memory has remarkable qualities: it preserves many aspects of our lives and expands our knowledge, abilities, and possibilities. It also has several notable limitations that largely make it non-transparent to us. As Schacter (2022) notes, these limitations are generally adaptive and should be thought of as ‘features’, not necessarily ‘bugs’. However, in some specific situations, they create erroneous or unwished-for consequences, more about it in part 3 below.

Takeaways: the conclusion is simple: if the knowledge is vital but its accessibility is uncertain, we have no choice but to check! To be absolutely sure about being able to use our knowledge and skills, we need to keep practising and checking until we can prove it is robust.

That’s about it. Don’t count on your memory unless you’ve checked it. As teachers, this is something we should take responsibility for, because our learners don’t always know what the goals are, and how to test for them. We should design the checks and plan a pathway to robustness when we decide it’s worth it.

If this sounds like formative assessment, retrieval practice and deliberate practice, then that’s exactly what it is. It is the educational way to deal with the cognitive terms and conditions. However, this is usually not as straightforward as it sounds. The next two parts delve into some of the core reasons:

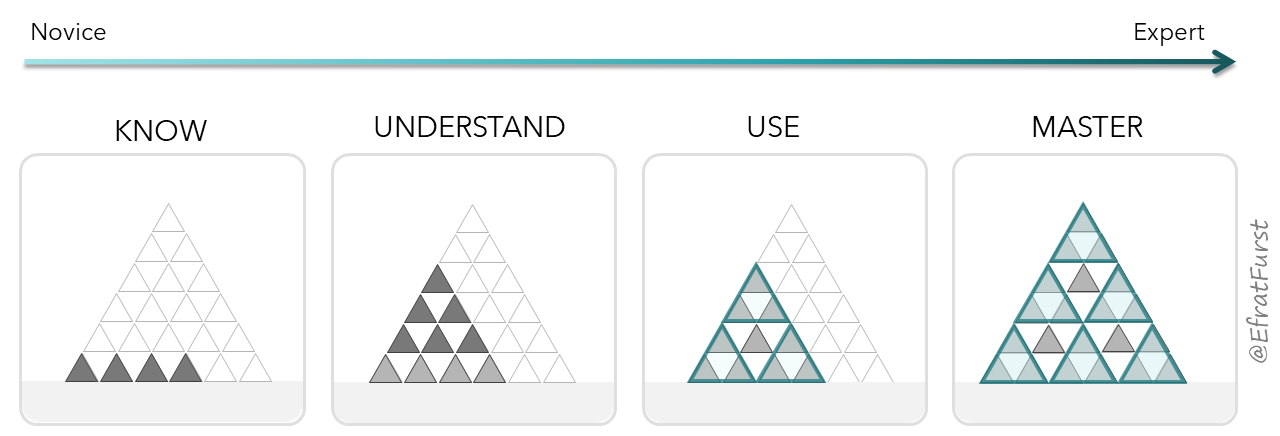

2. Learning happens in phases

Aligning learning with the functions and limitations of the cognitive system is crucial, but it is not a one-time thing; we use the cognitive systems iteratively, over time, to gradually deepen and broaden what we know and what we can do. Over time and learning opportunities, the way those systems interact changes, and we can identify different phases of learning.

Understanding the phases helps us make good choices about how to drive learning forward and focus on what is most helpful at a given stage. The learning pathways are not always clear (as we saw above), but relying on explicit definitions can help make more focused decisions. Researchers and practitioners have different ways to define those steps or phases, the models slightly differ in scope, definitions and purposes; however, the core ideas are largely aligned and based on similar evidence.

This is my way of understanding and explaining the phases of learning:

To learn a new component of knowledge (e.g. any new topic or sub-topic that includes some connected and organised knowledge and skills):

We start by considering prior knowledge. Everything is built on and with what we already know, this is what our brain works with to acquire new knowledge. Relevant prior knowledge should be intentionally identified and activated. On top of that, we are building something new, going through these phases:

Building blocks - the basic facts and concepts definitions, they might not be meaningful yet, but that doesn’t mean they are not necessary. Building blocks are the basic things that we know - the elements we build further with:

Making meaning - making meaningful connections between concepts is the “language of the brain”. Meaning organises our knowledge into semantic networks. We make meaning (“the penny drops”) when we “see” how concepts can become functional, even though they are not functional, yet:

Practice for function - ideas are not just there for their beauty or for our joy; we can and should learn how to use our connected ideas. We do so through practice, and what we practice can become functional and useful. We can put each semantic network or set of connected concepts to work in different ways: defining and practising the specific way(s) is the focus here.

Repeated variable practice towards mastery - the more, the longer, the more variable our practice is, the more functional and transferable our ability to use the knowledge becomes. Our level of mastery is dependent on the depth, breadth, repetiotions and dedication over time. With practice comes many benefits; one major benefit is automaticity - we invest less mental energy in what was once challenging, which makes us ready for the next cycle of more complex learning.

These are the phases, simple and generic. It is possible to delve into each of them, but for now, just a few important points:

These phases are not clear-cut; in fact, much planning should go into the gradual transition between them.

The above are only the cognitive considerations, a “mechanistic” view of how learning “works”. We can add layers and describe other aspects of each phase- specifically how motivation, cognition and meta-cognition combine and translate into choosing specific strategies.

Takeaway: This basic concept of “phases” is just a starting point for multiple branching considerations, but I find it both essential and helpful as a skeleton for planning and evaluating learning sequences. Breaking a complex, multifaceted sequence into apparent phases helps us make better decisions, per phase, and reduce our own cognitive load. We can focus on what is necessary and deflect the noise (such as “trendy” or “flashy” untested ideas).

This perspective highlights learning as a longitudinal process. As a learner, it is difficult, sometimes even impossible, to see the entire process clearly and make good decisions. As a teacher, you should see the goal clearly and plan the steps toward it. Seeing and naming the phases serves as a scaffold for this process.

At least that has been my experience: I look at any learning sequence through a “phases” lens, and this helps me see things clearly, even when they are complex. Over the years, I have used graphical models, like the one below, to describe these phases, and it is always good to hear that others find them helpful as well.

3. We don’t know how we learn

This third point is probably the most important one, because if we knew how we learn, we wouldn’t need cognitive science for teaching at all. In fact, we might not even need teachers. If, as learners, we could monitor and manage our learning process successfully, and consistently make the right choices for ourselves, content would probably be enough. But we don’t know, and content alone is not enough.

In learning, as well as in many other situations in life, we don’t always make the “right” or most logical decisions; we are often biased or unaware. Cognitive biases or illusions are adaptive responses to cognitive limitations in a complex environment and to the need to quickly respond to it. As such, they are an integral part of how we learn - and understanding how they function is essential for planning effective learning sequences.

Let’s briefly explore:

Why don’t we know?

Biases or illusions stem from the dynamics of our cognitive systems interacting with the environment, given their functions and limitations in a stimulus-saturated world. We have learned to respond as quickly and effectively as possible, despite our inability to process all the necessary information with adequate accuracy and speed. The cognitive limitations described in Part 1 above do not allow us to select from all incoming information, retrieve every relevant detail from memory, and process it effectively, logically, and consciously to produce a quick and rational response.

So, what do we do instead?

Fortunately, our cognition has adapted by developing shortcuts that elicit “reasonably good” responses. We select only the most prominent aspects of the environment and retrieve the most “retrievable” parts of relevant knowledge. Both processes are heavily dependent on prior experience and beliefs. We then make the “most probable” decision and act upon it. This allows us to respond quickly and effectively in many situations; the cost is getting it wrong in some of them. Researchers have identified many such situations, where the outcome is unexpected, illogical, or misaligned with intended goals, and have labelled them as various types of bias, illusion, heuristic, blind spot, or simply “effect.” This image lists dozens of them.

For example, the well-known confirmation bias is the tendency to interpret, prefer, or recall information in a way that confirms one’s existing beliefs. We do not invest equal processing resources in all items around us; we favour those we perceive as more prominent through our subjective lens - and we do so mostly unconsciously.

These biases, illusions, and effects are therefore the “cost” of adaptive behaviour that usually works well. We can make a conscious effort to overcome them in some scenarios, but certainly not in all, because doing so requires knowledge, awareness, effort, and processing power - cognitive resources that we simply cannot allocate constantly.

It should be noted that cognitive science is so effective at identifying these “effects” precisely because they are common to all of us. Our cognitive systems are limited in largely the same ways, and we therefore rely on similar compensation mechanisms. This is a powerful illustration of the extent of our cognitive similarities, and hence of the relevance of cognitive science to education.

How do bias and illusion work specifically in Learning?

When it comes to learning and remembering, it is not only our cognitive limitations (Part 1 above) that play a role. Another critical factor shaping our decision-making is the longitudinal nature of the learning process, and the fact that it unfolds through different phases over time (Part 2 above). This means that when we are learning in the present, we do not, and cannot, grasp what our experience will eventually turn into. We may have goals, but they are not concrete, because this is a path we have not yet travelled.

When it comes to making good learning decisions, two major conflicts emerge:

We cannot process all relevant information and knowledge, so we rely on shortcuts: feelings, impressions, and beliefs, as we do with many other cognitive biases. For example, when we reread a passage, and it makes general sense, that feeling is often enough to make us feel confident. We are not actively exploring the deep structures of understanding, evaluating contradictory information, or testing alternative interpretations; our cognitive resources are focused on what is immediately available and demanding.

In the present moment, it’s difficult, if not impossible, to predict the future and align our actions with future goals, so we rely on currently available active cues.

To continue the example: while reading, we are not imagining how this content might help us win a debate on a similar topic in a month’s time. We also cannot predict what we will remember or what we will be able to do with this knowledge by then.

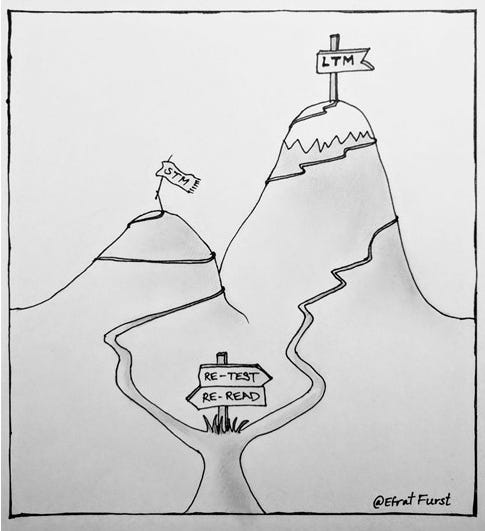

There is nothing in the present experience that signals the need to do something different. This short-term–long-term paradox in learning introduces an additional layer of complexity, one that is closely tied to the different phases of learning and to how we emotionally and behaviourally respond to them.

The make meaning phase can be quite pleasing (when the level is right): understanding new ideas is immediately rewarding. Repeating the same ideas in different ways to deepen our understanding and exploring examples is even more rewarding - especially when the sequence is well constructed, and when the teacher is great. This is known as the fluency bias that creates an illusion of learning (Bjork et al., 2013). Repeating this behaviour is rewarding and can even be easily shaped into a habit (Krause et al., 2025).

The practice for function phase, on the other hand, is more challenging, less clear, not always successful, and therefore inherently less rewarding, certainly not immediately. Repeated immediate rewards play an important role in shaping human behaviour. Together, this leads to a third important point about learning:

The cues available in the present, on which we rely for decision making - the feelings and rewards the learning experience produces- strongly favour staying in the meaning-making phase rather than entering the practice phase (Carpenter et al., 2022). This is likely one reason we don’t choose effective strategies even when we know we should: habit wins (Krause et al., 2025).

Together, these three factors—limited processing resources, inherent short-sightedness, and reward-driven behaviour—push us in the same direction. When choosing what to do next, we tend to choose what is familiar and immediately rewarding rather than what is unfamiliar and effortful. The vague future goal, no matter how theoretically positive, plays only a small and practically insignificant role in this “shortcutted” decision-making process.

This pattern has been identified repeatedly in learning research and was famously described by Bjork & Bjork(2011) as desirable difficulties: the tension between valued long-term goals and the inherent difficulty of achieving them.

A hiking analogy fits nicely here. Imagine a hike to a mountain peak, where the highlight is the breathtaking view. Without a guide, you might choose the path that feels most comfortable at every turn, only to find yourself nowhere near the summit. A guide, however, leads you through challenging but manageable climbs toward the view you actually set out to see. Making many local, on-the-spot “feel-good” choices does not lead to the goal. Learning works in the same way: it needs guidance toward long-term goals.

Years ago, I sketched this to illustrate the choice between self-testing and rereading:

There are several types of biases and illusions that are specific to learning and teaching. While they can be explored independently, their general effect is largely similar: they make it difficult for both learners and teachers to see the learning pathway clearly and to make better choices at critical, challenging turns.

To sum it all up:

Why is cognitive science important? What can we learn from it, and how is it helpful?

Cognitive science is the body of evidence about how learning works. We need it because, although we learn all the time, we do not really know how learning works. Learning is natural, but it is not intuitive. This is why teachers are needed to achieve challenging learning goals - and why teachers themselves need to learn and deliberately practice to be effective.

Cognitive science provides the evidence we need to understand the universal processes of learning. It does not simplify teaching, but it clarifies where the blind spots are and at which critical turns along the learning pathways the learning–teaching interaction matters most: when cognitive systems meet their limitations (each becoming more prominent at different phases), when adaptations for quick responses shortcut deeper thinking processes, and when immediate rewards overshadow long-term goals, teachers can and should:

Help learners filter and focus both relevant prior knowledge and incoming information, especially at initial stages, when learners do not yet have the tools to manage this process themselves.

Move learners along the phases of learning, using and introducing the most relevant strategies at each point, particularly when the right choice is neither trivial nor intuitive.

Design frequent checkpoints—opportunities to “test” what knowledge is available and accessible, how it can be used, and to guide further practice toward robustness.

Plan for expected desirable difficulties—making difficult choices possible, and even necessary, by using rewards wisely towards a long-term goal.

Cognitive science also provides evidence for some of the most effective strategies in these situations. These are universal findings that build on the basic scientific understanding of learning. Making them work in practice is what teachers do: translating evidence into classroom design, while integrating professional judgment, content knowledge, and context-specific considerations. This is a challenging task, which is why structured and well-designed learning sequences for teachers’ professional learning are crucial as well.

When this work is done well, learners learn better - and they learn more than just the subject matter. When long-term goals are achieved, learners also learn about the nature of the learning process itself (what we call metacognition). With accumulating experience, they gain the ability to navigate challenging learning pathways independently - we call this self-regulated learning (But even experienced learners still need a good road map).

In future posts, I plan to write more in the space where cognitive evidence meets classroom practice. This evidence-informed, classroom-oriented perspective takes cognitive science seriously and translates it with teachers and learners in mind. I hope it resonates with those of you who teach and see this as part of your professional development pathway - from all the reasons explored here.

References:

(in order of appearance)

Kirschner, P., Sweller, J., & Clark, R. E. (2006). Why minimal guidance during instruction does not work: An analysis of the failure of constructivist, discovery, problem-based, experiential, and inquiry-based teaching. Educational psychologist, 41(2), 75-86.

Clark, R. E., Kirschner, P. A., & Sweller, J. (2012). Putting students on the path to learning: The case for fully guided instruction. American educator, 36(1), 6-11.

Tulving, E. (1985). Memory and consciousness. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie canadienne, 26(1), 1.

Schacter, D. L. (1999). The seven sins of memory: insights from psychology and cognitive neuroscience. American psychologist, 54(3), 182.

Schacter, D. L. (2022). The seven sins of memory: An update. Memory, 30(1), 37-42.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cognitive_bias

Bjork, R. A., Dunlosky, J., & Kornell, N. (2013). Self-regulated learning: Beliefs, techniques, and illusions. Annual review of psychology, 64(1), 417-444.

Krause, A. K., Breitwieser, J., & Brod, G. (2025). Understanding Learning Strategy Use Through the Lens of Habit. Educational Psychology Review, 37(4), 109.

Carpenter, S. K., Pan, S. C., & Butler, A. C. (2022). The science of effective learning with spacing and retrieval practice. Nature Reviews Psychology, 1(9), 496-511. - Especially Box 1 and Figure 6.

Bjork, E. L., & Bjork, R. A. (2011). Making things hard on yourself, but in a good way: Creating desirable difficulties to enhance learning. Psychology and the real world: Essays illustrating fundamental contributions to society, 2(59-68), 56-64.

This is a strong first post — not because it simplifies cognitive science, but because it clarifies why teachers actually need it.

What I appreciated most is your insistence that learning is natural but not intuitive. That single idea explains so much classroom frustration: why students feel confident but can’t retrieve later, why rereading feels productive but isn’t, why effortful practice is resisted even by motivated learners. You make the case that cognitive science isn’t about adding techniques; it’s about revealing the blind spots that mislead both learners and teachers.

Your framing of learning as phased is particularly useful. It gives teachers a way to diagnose what kind of help is needed now, rather than defaulting to whatever strategy feels familiar or fashionable. That alone reduces noise, cognitive load, and decision fatigue — for teachers as much as for students.

This is one of the greatest articles of all time: “Kirschner, P., Sweller, J., & Clark, R. E. (2006).”